John Andrew BAINBRIDGE

Eyes brown, Hair dark, Complexion dark

Jack Bainbridge – Wounded at Gallipoli, Died at Fromelles

Can you help find Jack?

John Andrew Bainbridge’s body was never found after the Battle of Fromelles, and there are no records of his burial.

A mass grave was found in 2008 at Fromelles, a grave the Germans dug for 250 Australian soldiers they recovered after the battle. As of 2024, 180 of these soldiers have been able to be identified via DNA testing.

Jack may be among these remaining unidentified men. There is still a chance to identify him — but we need help. We welcome all branches of his family to come forward to donate DNA to help with his identification, especially those with roots in Newcastle, NSW

See the DNA box at the end of the story for what we do know about his family.

If you know anything of contacts for John Andrew, please contact the Fromelles Association.

Please contact the Fromelles Association of Australia to find out more.

Early Life

John Andrew “Jack” Bainbridge was born on 7 August 1887 in Newcastle, New South Wales, the youngest of seven children of Thomas James Bainbridge and Jane Anne (née Cooper). His parents were coal mining stock from Durham, England. His father, Thomas, was born in Wingate in 1846, and his mother, Jane, around 1851 in Shincliff. In 1878, Thomas and Jane emigrated to Australia aboard the Ironside, arriving in Moreton Bay, Queensland, with their two small sons, Henry and Benjamin.

They were accompanied by members of Jane’s extended Cooper family, including her mother Ann, two sisters (Margaret Smith and Elizabeth Richardson), and her brother Benjamin. The family soon settled in Newcastle, where mining work was plentiful. Thomas and Jane went on to have five more children in Australia:

- James William (1880–1881)

- Alice Ann (1881)

- James (1884–1884)

- Joseph (1885)

- and finally John (Jack) in 1887

Two of these children died in infancy, leaving Jack as the youngest of five surviving siblings. Tragedy struck early in Jack’s life. His mother Jane died in 1889 when Jack was only two years old, leaving Thomas with several children to care for. His maternal aunt, Elizabeth Richardson (née Cooper), stepped in to raise the younger children, and after Thomas’s own death in 1905, she became Jack’s full-time guardian.

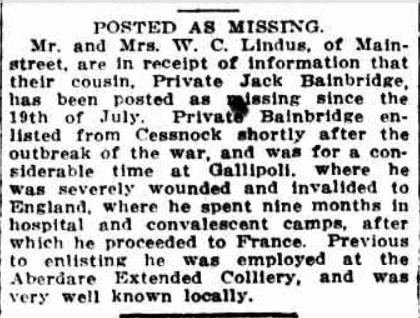

In correspondence with military authorities, Elizabeth referred to Jack as her “dear boy,” and at times he was even recorded under the surname Richardson, reflecting the closeness of their bond. Before enlisting, Jack worked as a labourer at the Aberdare Extended Colliery in Cessnock.

Off to War

Jack enlisted at Liverpool, New South Wales, on 23 January 1915, aged 27. Though under the usual height requirement, his fitness as a colliery labourer helped secure his place in the AIF. He was taken into the 1st Battalion and embarked from Sydney on 25 June 1915 aboard HMAT Ceramic.

Jack at Gallipoli

Too late for the ANZAC landing, he reached Gallipoli in time for the August offensive, including the brutal fighting at Lone Pine. On his 28th birthday – 7 August 1915 – he was severely wounded in the right thigh and evacuated first to Malta and then to England, where he spent months recovering.

His experience at Gallipoli is best remembered in his own words. In a letter to his cousin and foster-brother Ralph Richardson — later published in a Sydney newspaper along with his photograph — Jack gave a stark account of the battle:

Under fire

“My first time under artillery fire I can’t tell actually what it felt like. I was just like a man in a dream. When the word came to charge all fear left me. It was just like hell let loose. The bullets, shrapnel, and machine gun fire were awful. You would think the world was on fire. Oh! and those shells bursting all around you. One of our poor chaps was completely blown to pieces by a shell.”

An unforgettable birthday

“When I got hit it was about 3 o’clock in the morning of August 7. My birthday, so I won’t forget it for some time. … I’ll never forget the night before I was wounded. In our trench, we were firing rapidly from about 5 o’clock till I was hit the next morning. The Turks were bombing us all night. Our trench was full of dead and the moaning and groaning were awful to hear.”

Respect for comrades and enemies alike

“They were only 20 yards away from our trenches … they are good shots, but they won’t face the bayonet and I tell you the Australians and New Zealanders are the boys with the bayonet. We have lost pretty heavily, but the Turks’ losses are enormous. Out of our battalion of 700 only about 100 returned.”

Evacuated to England

“I was three weeks in St Elmo Hospital in Malta, that is four days sail from the Dardanelles, and then they sent a lot of us to the hospital in Surrey, England. It is only 12 miles from here to London. It is a beautiful building; there are seven miles of corridors in it, so you can imagine what it is like.”

Jack spent nearly eight months in hospitals and convalescent camps before being declared fit. By April 1916, he was posted to the 53rd Battalion in Egypt, preparing for service on the Western Front.

After his recovery from Gallipoli, Jack was transferred to the newly formed 53rd Battalion on 20 April 1916. The battalion was created as part of the “doubling” of the AIF, with half its ranks filled by Gallipoli veterans from the 1st Battalion (like Jack) and the other half by reinforcements newly arrived from Australia. On 8 July the 53rd Battalion began a 30-kilometre march to Fleurbaix, arriving and settling into billets on 16 July. The next morning, they moved into the trenches to relieve the 54th Battalion in preparation for an attack. A planned advance was cancelled due to bad weather, but by 19 July they were again in position and ready.

Private Jim Granger recalled the tension before the attack:

“We were held in suspense for three days… like a criminal waiting to hear the verdict.”

Battle of Fromelles

The 53rd’s objective was to take trenches to the left of a heavily fortified German strongpoint known as the Sugar Loaf. This elevated position dominated No-Man’s-Land and enfiladed the Australian advance with machine-gun fire. The battalion advanced in four waves: half of A and B Companies in the first two, C and D in the third and fourth. By late morning, both sides were engaged in heavy bombardments.

At 4:00 p.m., the 54th Battalion rejoined the line on the 53rd’s left. Zero hour was set for 5:45 p.m., but the Germans anticipated the attack and opened a furious artillery barrage at 5:15 p.m. Rather than charging, they first moved into No-Man’s-Land and lay waiting for the bombardment to lift. At 6:00 p.m., they rushed the German lines under intense artillery, machine-gun and rifle fire.

Corporal J.T. James (3550, C Company) later recalled:

“At Fleurbaix on the 19th July we were attacking at 6 p.m. We took three lines of German trenches.”

The 14th Brigade War Diary noted:

“Very few living Germans were found in the first and second line trenches.”

But success came at a terrible cost. Within 20 minutes, the 53rd had lost all company commanders, all seconds-in-command, and six junior officers. Despite linking up with the 54th on the left and 31st/32nd Battalions near Delangre Farm, the failure to take the Sugar Loaf left the 53rd’s right exposed. That night, German forces re-entered the original Australian front-line trench, getting behind the 53rd’s position.

They fought through the night, digging in, repelling attacks from the front, and eventually battling their way back. The battalion was ordered to withdraw by 9:00 a.m. on 20 July. By 9:30 a.m., they had retired from the line, suffering what the unit diary described as:

“Very heavy loss… Many heroic actions were performed.”

Private Arthur Crewes later wrote of the charge:

“Over the top we went into the face of death… shells bursting, machine guns rattling and rifles crackling… From my shelter I could see our lads rushing on in the face of death. It was a fine though terrible sight.”

At roll call, just 36 men answered their names from the 990 who had landed in Egypt. The final toll for the 53rd Battalion was 245 killed or died of wounds, 190 of whom have no known grave.

Jack Bainbridge was one of them. His fate was described by his comrades.

1336 Private John Allen Cumming, 53rd Battalion:

`“I saw him badly wounded and lying in the German 2nd line trench at Fleurbaix on July 19th. We held this trench for some time, and then had to evacuate it. He had to be left there. He was pretty bad … wounded in the leg and head. He may be a prisoner, but more likely he died of wounds.”

Source: AWM Red Cross Wounded and Missing Files – John Andrew Bainbridge, p.2

3413 Daniel Michael Regan:

“I saw him lying badly wounded on the German parapet at Fromelles (?) in the advance. I heard since from Cumming, A. 53 D., that he died.”

Source: AWM Red Cross Wounded and Missing Files – John Andrew Bainbridge, p.3

After the Battle

Jack was last seen badly wounded during the fighting of 19 July 1916. Witnesses told the Red Cross he had been left behind in the German second line trench, or lying on the parapet, gravely injured. He was never seen again. Like so many of his comrades, Jack has no known grave.

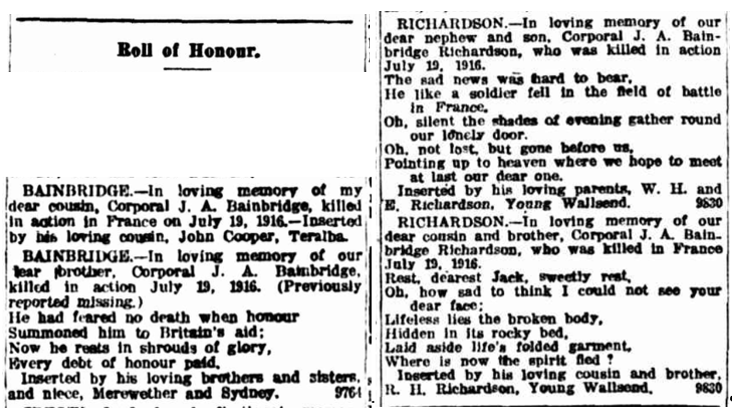

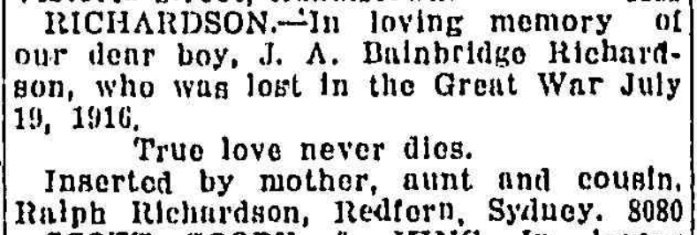

For his foster-mother, Elizabeth Richardson of Young Wallsend, the loss was deeply personal. She corresponded with the authorities after the war, always referring to Jack as her “dear boy.” Her devotion ensured his service and sacrifice were not forgotten, even when his remains could not be recovered.

Jack’s name was listed among the fallen in local memorial notices, and his sacrifice is commemorated at:

- V.C. Corner Australian Cemetery and Memorial, Fromelles, France – panel no. 7, among 410 Australians with no known grave.

- Australian War Memorial, Canberra – Roll of Honour, Panel 42.

- Young Wallsend Roll of Honour – local community roll.

- West Wallsend Soldiers’ Memorial – corner of Carrington and Hyde Streets.

- Cessnock War Memorial – North Avenue, Cessnock.

- Sandgate Cemetery, Newcastle – memorial cross placed on his parents’ grave (Jane and Thomas Bainbridge) after the original headstone was destroyed.

Decades later, his memory was honoured again when a memorial cross adorned with poppies was placed on his parents’ grave at Sandgate Cemetery, Newcastle, after the original headstone had been destroyed. The tribute was recorded on the Northern Cemetery website as a permanent reminder of his service.

Finding Jack

The search for suitable DNA donors was not the easiest. Of the five Bainbridge siblings to survive to adulthood, only the eldest (Thomas Henry) married and had children. After writing to all the Bainbridges listed in the Newcastle area telephone book, it was still difficult to identify a likely connection on the male line.

In the meantime, however, a search on Trove enabled our researcher to identify a likely connection between the Bainbridge and Lindus families. John’s maternal cousin, Elizabeth Smith (daughter of his mother’s older sister - Margaret Smith, nee Cooper), had married Bill Lindus in 1901. After writing to the Lindus families, a reply from a lady well versed in the family’s history led to our researcher contacting family connections who were excited to hear of the search on Jack’s behalf and willing to provide the necessary Mt DNA samples.

Our researcher was still however actively seeking a suitable donor on the YDNA line, going back several generations and working through numerous roadblocks and red herrings. After two years of researching – to the day – a submission was made to the army with details of a direct line. To date, identification has not been confirmed and the search continues.

DNA samples are being sought for family connections to

| Soldier | John (Jack) Andrew Bainbridge (1887–1916) |

| Parents | Thomas James Bainbridge (1846–1905, Wingate, Durham, England – Newcastle, NSW) and Jane Anne Cooper (1851–1889, Shincliff, Durham, England – Newcastle, NSW) |

| Siblings | Henry Bainbridge (1875–1946) | ||

| Benjamin Bainbridge (1877–1938) | |||

| Alice Ann Bainbridge (1881–1962) | |||

| Joseph Bainbridge (1885–1954) | |||

| Two Siblings died young |

| Grandparents | |||

| Paternal | James Bainbridge (b.1822 Durham – to Australia 1858, collier, death unknown) and Alice Barnett/Barrett (1825–1896, Durham, England) | ||

| Maternal | Benjamin Cooper (c.1817, Durham, miner) and Ann Richardson (c.1819–1896, Durham – Newcastle, NSW) |

Links to Official Records

Seeking DNA Donors

Contacts

(Contact: carla@fromelles.info or geoffrey@fromelles.info).

(Contact: army.uwc@defence.gov.au or phone 1800 019 090).

Donations

If you are able, please contribute to the upkeep of this resource.

(Contact: bill@fromelles.info ).